Toptana Technologies – a self-funded enterprise owned by the Quinault Indian Nation (QIN) – is emerging as a leader in Washington’s broadband expansion as it works to build the state’s first new cable landing station (CLS) in over 20 years.

The QIN is a sovereign Tribal community of more than 3,000 people located along the coast of Washington state. Toptana launched in 2021 but has been “in the works” since as early as 2017, according to Tyson Johnston, the policy representative and former VP of the QIN. Johnston has served in elected office for the past decade and is the head of development for Toptana, where he leads the company’s subsea CLS and terrestrial network project.

About one-third of the QIN community lacks internet access of any kind. Those with access have had to rely on slow, unreliable microwave signals provided by the Tribe that top out around 10 Mbps, “a fraction of what industry standard speeds are,” he noted, with 25 Mbps the minimum set by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

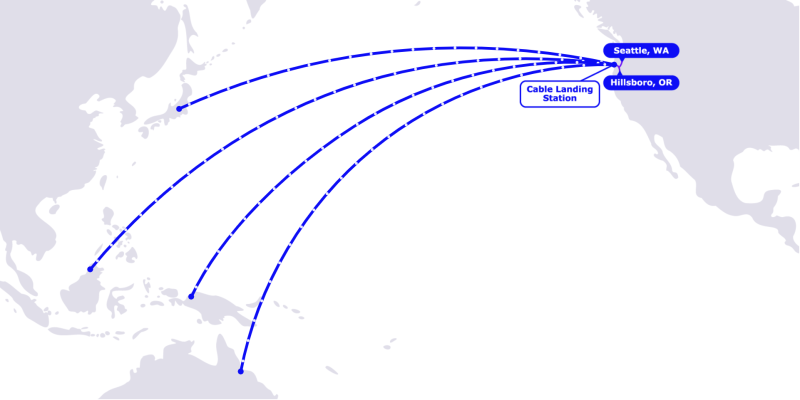

A CLS is a facility where undersea or submarine telecommunication cables come ashore (in this case connectivity travels all the way from Asia-Pacific markets) and backhaul to terrestrial network infrastructure.

The backhaul network from Toptana’s CLS will provide fiber in communities along a 79-mile east-west stretch on Washington’s Interstate-5, reaching not only into tribal land, but also across rural communities neighboring the QIN.

“It just made sense to take a multifaceted approach and not only prioritize addressing the Quinault Nation's unique need, but also turn this into an opportunity that could bring vitality to a really depressed region and provide connectivity to communities that are either not receiving any service or are extremely underserved at the moment,” Johnston told Fierce.

Toptana’s backhaul network will bring dark-fiber options for local providers in all Grays Harbor County’s main communities and into Lewis County. In the rural areas of Grays Harbor County, roughly 80% of residents either have substandard or no internet, including those on the QIN reservation.

Toptana also acquired fiber that goes north to Seattle and south to Hillsboro and Portland, Oregon which it will develop once the east-west deployment is complete.

The new CLS will be able to host up to four subsea customers, with capacity for up to eight, or as many as 16 if Toptana chooses to expand in the future.

Toptana’s subsea project has required “a lot of relationship building these last several years,” Johnston said, and the company has “amassed a pretty great network of industry partners.” Among those partners is Assured Communications, which is the service entity that will be operating the CLS and coordinating the sales function of Toptana.

While the company is open to partnering with larger providers for the backhaul network, Toptana “definitely wants to emphasize local providers,” Johnston added. He couldn’t disclose any specific providers that Toptana plans to work with, but Johnston told Fierce that the project is in the late design stages with hopes to be completed in under three years.

Toptana and the QIN stand as unique stakeholders in broadband expansion, which is why they were able to secure one of the region’s first CLS projects in over two decades. As of now, Toptana is the only indigenous-owned cable landing station and backhaul network provider on the West Coast of the U.S.

One reason there haven’t been any new CLS buildouts in Washington is the state's cumbersome environmental analysis and permitting process, Johnston said.

But the Tribe’s “unique status and experience working through environmental processes and our own natural resources, management practices and values” puts the QIN and Toptana in a good position to navigate those spaces and move through Washington’s processes quicker than other enterprises can.

Quinault is one of four tribes in the whole country that has adjudicated ocean rights in the Pacific Ocean. The QIN is a self-regulatory tribe that has a unique governance relationship with its territory and waters, which puts the Tribe “on equal standing to the state and at a nation-to-nation type of level with the federal government,” Johnston explained.

“So, we're avoiding that additional complication that exists to get these projects within the timeline that's expected by the industry,” he added. “Because usually, these things -- cable landing on both sides of the Pacific -- are expected to be developed over a two to three year period. And if you're not able to meet that timeline, it's hard to get industry to justify a site location in an area like ours.”

Johnston said Toptana is making sure it does its due diligence in keeping the project’s ecological footprint minimal. For example, there is a marine sanctuary that encompasses a large section of the marine environment off the coast of Washington, and Toptana will ensure the CLS access point is built outside of the sanctuary.

While Toptana has presented the subsea project as "Environmental, Social and Governance-centric" (ESG), Johnston noted that for the Quinault Nation, environmental stewardship and preservation are core values -- not just an ESG play.

“That's fundamental to who we are as a tribal people,” he added. “We're a Pacific Ocean people, we're fishing people. We have been co-managing and self-governing pretty vast natural resources for time immemorial -- huge forests, river systems, lakes, and the ocean. When we've seen other projects that have a large ecological footprint or could be potentially harmful to the environment, we've been very critical, making sure that things that do develop in our area don't put our resources at greater risk. Not only from the environmental perspective, but from a cultural and spiritual identity, those values are intrinsic to who we are.”

To further expedite Toptana’s work, Johnston also worked this past legislative session at the state level to receive a bill that effectively grants a state sales tax exemption on the construction activities of the subsea project. That legislation passed, resulting in an exemption of up to $8 million on sales tax related to Toptana's construction activities.

Johnston said Toptana will also be looking down the pipeline to see if any funding from Washington's Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) allocation will be made available for the project, in addition to “other tribal opportunities and funding opportunities.”

“We're always on the lookout for those, but it's really hard to see funding opportunities fall in line with project timeline,” he said. “So we're not putting a lot of stock in those, but we're definitely going to be pursuing them as they become available.”

Johnston noted in a Toptana blog that the ongoing digital isolation in the QIN’s region has worsened as the world relies more on digital access and the Internet of Things (IoT). With the introduction of broadband, Quinault artisans and rural businesses can launch e-commerce shops, connect to potential customers, and promote themselves online. Smart appliances and security gadgets will enhance home living, while the presence of Toptana's CLS will prioritize power restoration in the community and offer new revenue streams for the Quinault Nation.

Keeping the CLS and surrounding port safe would also potentially mean the installation of a sensor in the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which would measure seismic activity while providing advanced warning for the region during natural disasters, he added.

“Without proper access to the technology and broadband infrastructure in our area, it is nearly impossible under today's conditions to have a vital economy, established educational equity in schools and improved health care,” Johnston told Fierce.