As telcos work on their sustainability efforts, Zayo Group is working with universities to find clean energy alternatives. Researchers from Rice University are leveraging Zayo’s dark fiber to locate and monitor geothermal resources, or heat produced below the earth’s surface.

Rice University collaborated with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on the Imperial Valley Dark Fiber Project, an initiative that kicked off in 2019 and was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

The project, which Zayo last week announced was completed, focused on the use of dark fiber as seismic sensors to get a better sense of where geothermal resources are located. Analysis of the data is still very much underway, according to Dr. Jonathan Ajo-Franklin, one of Rice University’s researchers on the project.

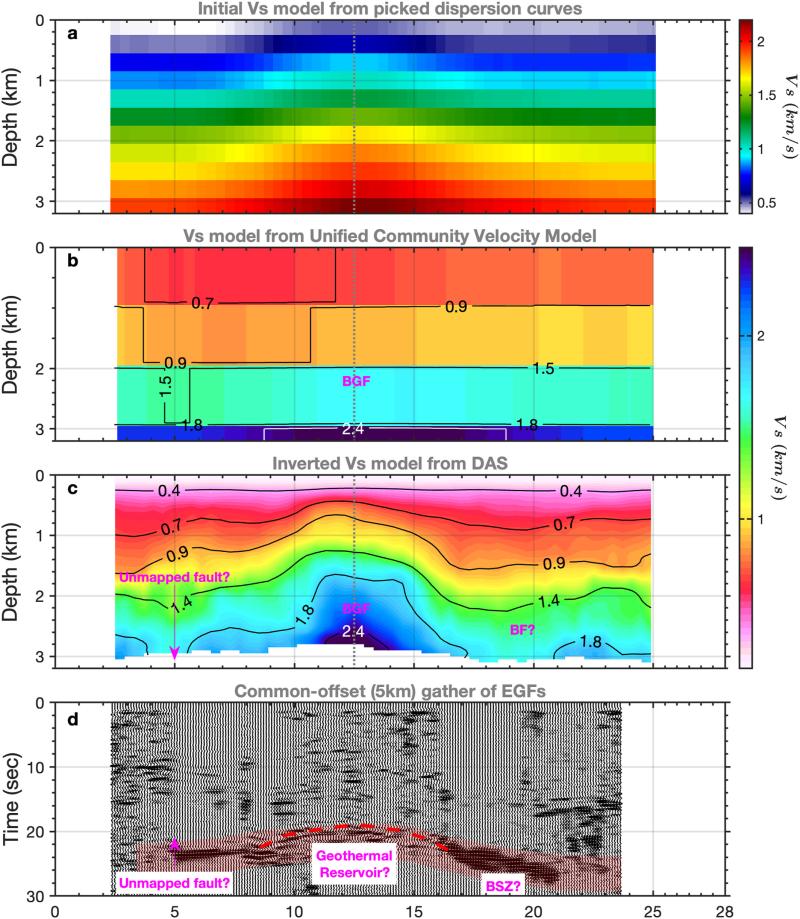

He explained the Imperial Valley initiative (which took place in the Southern California region of the same name) involved the use of Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS), “which basically allows you to use fiber optics to record small vibrations underground using a very high-speed pulse laser.”

Essentially, DAS let the researchers “listen” for the geothermal sources.

Instead of digging trenches and installing their own fiber for the research, which can be time-consuming and costly, Ajo-Franklin’s team got the idea to use fiber from existing telecom networks.

So, in 2019, Rice University tested its DAS technology on a stretch of fiber from ESnet, a network that serves DOE scientists and researchers. The fiber was located in California’s Sacramento Basin.

“It worked really well,” Ajo-Franklin told Fierce. “We got some good signs, we were able to detect some earthquakes and build pictures of what the near surface looked like in that area.”

One of the challenges of looking for geothermal energy reserves is that many basins are “poorly explored,” so there isn’t much traditional data available that would explain how to find them. He noted dark fiber is well-suited for picking up ambient noise and using it to create a picture of what’s underground.

After Ajo-Franklin’s team (dubbed the Berkeley Lab-Rice team) applied for funding from the DOE, they set out to find a dark fiber provider to collaborate with. Zayo, he said, “kind of fit all our constraints.”

Zayo’s role

For starters, Zayo has existing dark fiber infrastructure in Imperial Valley – enough that “allows for that testing to be done,” said Jason Taylor, Zayo’s SVP of Enterprise Sales.

Like other dark fiber providers, Zayo sells it to commercial customers and government agencies. But in this case, Zayo’s dark fiber allowed the Berkeley Lab-Rice team “to connect the equipment that they needed on both ends to do the monitoring.”

Taylor told Fierce Zayo “gets a lot of attention” from government agencies due to the amount of dark fiber the company possesses. Zayo has said its long-haul network spans over 17 million fiber miles and 142,000 route miles.

“In this instance, it was really taking a small piece of a long-haul route and using it for a different use case than what we normally look that,” Taylor said.

He called out since the project kicked off, Zayo had “multiple research institutions” reach out to ask questions about the work that went into it, “so this could lead to other test trials being ran and maybe more information being learned.”

The “most exciting” element of this project, Taylor went on to say, was “support[ing] a mission that positively impacts the environment.”

“It’s something that’s a priority for us as it is [for] a lot of corporations, and this was a way we could show our support in a real way that should have a positive impact going forward,” he said.

The Berkeley Lab-Rice team also leveraged Zayo’s dark fiber to test earthquake detection. The Imperial Valley project “recorded a tremendous amount of earthquakes which aren’t picked up by the regional catalog,” said Ajo-Franklin.

Those smaller earthquakes, he explained, helped the researchers determine “where there might be places for water to flow underground for geothermal production.”

Additionally, the team used its findings to build an accurate model of “the velocity of seismic waves underneath the entire basin.”

“That’s the kind of thing which is really useful in sort of choosing the next place you might want to consider for exploration,” Ajo-Franklin said.